Family Ages Investigation: Subtraction on an Open Number Line

- Zip

Description

This digital download includes a unit on subtraction (5 lessons) based upon the educational resource by Catherine Twomey Fostnot - Ages and Timelines: Subtraction on the Open Number line.

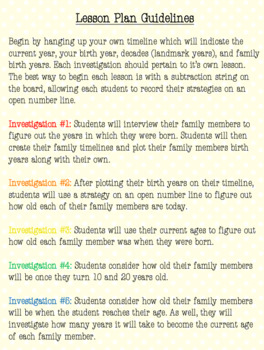

Children interview their family members and compare age differences. Timelines are introduced as a context for using the open number line - a helpful model used as a tool to explore and represent strategies for addition and subtraction. This unit will focus on the open number line as a model for subtraction.

This unit begins with the reading of the story: El Bisabuelo Gregorio. A story of Carlos, an eight-year-old boy who is fascinated by his great-grandfather's thick, beautiful silver hair. His great-grandfather lives in Puerto Rico and Carlos is preparing to meet him for the first time. Having only seen photos of him as a much younger man, Carlos wonders how old his great-grandfather is and how many years it will take before he might have hair like that, too. As Carlos begins to investigate these questions, his whole family becomes involved in exploring age differences and figuring out how old they each were when Carlos was born. When Carlos shares his investigation with his teacher, the whole school gets involved in the project.

This story context sets the stage for a series of investigations in this unit. Children interview their family members and compare age differences. Timelines are introduced as a context for using the open number line - a helpful model used as a tool to explore and represent strategies for addition and subtraction.

Please rate and leave feedback!

- Hal's Hallway